The Gospel of John is one of the four narratives of the Christian gospel included in the canon of scripture. It is known that none of these books had a proven authorship, but it is traditionally believed that each gospel is written by the four disciples of Christ - the apostles. Even according to the testimony of the bishop of Lyon, Irenaeus, a certain Polycrates, who personally knew John, claimed that he was the author of one of the versions of the Good News. The place of this Gospel in theological and theological thought is unique, because its text itself is not only and not so much a description of the life and commandments of Jesus Christ as an exposition of His conversations with the disciples. Not without reason, many researchers believe that the narrative itself developed under the influence of Gnosticism, and among the so-called heretical and unorthodox movements it was very popular.

Interpretation of the Gospel of John in the Early Period

Christianity until the beginning of the fourth century was not a dogmatic monolith, rather, a teaching previously unknown to the Hellenic world. Historians believe that the Gospel of John was the text that was positively received by the intellectual elite of antiquity, as it borrowed its philosophical categories. This text is very interesting in explaining the relationship between spirit and matter, good and evil, peace and God. No wonder the prologue, which opens the Gospel of John, refers to the so-called Logos. “God is the Word,” the author of the Scriptures openly declares (Gospel of John: 1.1). But the Logos is one of the most important categorical structures of ancient philosophy. One gets the impression that the real author of the text was not a Jew, but a Greek who had an excellent education.

Question about Prolog

The beginning of the Gospel of John looks very mysterious - the so-called prologue, that is, chapters 1 to 18. Understanding and interpreting this text over time has become that stumbling block within Orthodox Christianity, on the basis of which the theological foundations of the creation of the world and theodicy are derived. For example, take the famous phrase, which in the synodal translation looks like “Everything began to be through Him (that is, God), and without Him nothing happened that arose” (John: 1,3). However, if you look at the Greek original, it turns out that there are two oldest manuscripts of this Gospel with different spelling variations. And if one of them confirms the orthodox version of the translation, the second sounds like this: "Everything through Him began to be, and without Him nothing came about." Moreover, both versions were used by the church fathers in early Christianity, but subsequently it was the first version that entered the church tradition as being more “ideologically true”.

Gnostics

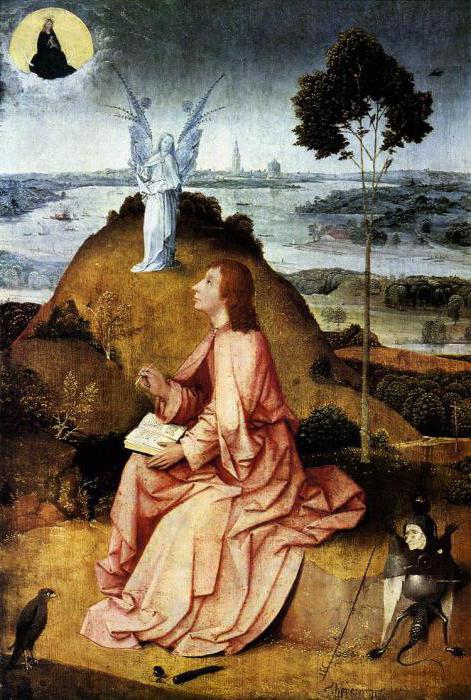

This fourth gospel was very popular among various opponents of the orthodox dogmas of Christianity, who were called heretics. In the days of early Christianity, they were often Gnostics. They denied the bodily incarnation of Christ, and therefore many passages from the text of this Gospel, justifying the purely spiritual nature of the Lord, came to their taste. Gnosticism also often contrasts God “above the world” and the Creator of our imperfect being. And the Gospel of John gives reason to believe that the rule of evil in our lives does not come from the Heavenly Father. It often refers to the confrontation between God and the World. Not without reason, one of the first interpreters of this Gospel was one of the disciples of the famous Gnostic Valentine - Heracles. In addition, among the opponents of orthodoxy, their own apocrypha were popular. Among them were the so-called “Questions of John,” which spoke of secret words that Christ said to his beloved disciple.

"A masterpiece of Origen"

So called the comments of the ancient theologian to the Gospel of John, the French explorer Henri Cruzel. In his work, Origen criticizes the Gnostic approach to the text, while extensively quoting his opponent. This is an exegetical composition in which the famous Greek theologian, on the one hand, opposes unorthodox interpretations, and on the other, he himself puts forward several theses, including those concerning the nature of Christ (for example, he believes that a person should move from his own essence to an angelic one), which were subsequently deemed heretical. In particular, he also uses the variant of translation Ying: 1,3, which was later recognized as inconvenient.

Interpretation of the Gospel of John Chrysostom

Orthodoxy is proud of its famous interpreter of Scripture. It is rightfully John Chrysostom. His interpretation of this gospel is included in an extensive work on the interpretation of the Scriptures, starting with the Old Testament. He shows great erudition, trying to reveal the meaning of each word and sentence. His interpretation plays a predominantly polemic role and is directed against opponents of Orthodoxy. For example, the above-described version of the translation of John: .1.3 John Chrysostom finally recognizes heretical, although before him it was used by the respected Church Fathers, in particular, Clement of Alexandria.

When the gospel was interpreted politically

This may sound surprising, but the interpretation of Scripture was also used to justify mass repressions, annihilation of objectionable people and hunting for people. This phenomenon is most clearly manifested in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. During the formation of the Inquisition, chapter 15 of the Gospel of John was used by theologians to justify the burning of heretics at bonfires. If we read the lines of Scripture, they give us a comparison of the Lord with the vine, and his disciples with the branches. So, exploring the Gospel of John (chapter 15, verse 6), you can find words about what should be done with those who do not abide in the Lord. They, like branches, are cut off, collected and thrown into the fire. Medieval lawyers of canon law managed to interpret this metaphor literally, thereby giving the go-ahead to cruel executions. Although the meaning of the Gospel of John completely contradicts such an interpretation.

Medieval dissidents and their interpretation

During the reign of the Roman Catholic Church, it was opposed

The so-called heretics. Modern secular historians believe that these were people whose views differed from the “dictated from above” dogmas of the spiritual authorities. Sometimes they were organized into communities, which also called themselves churches. The most formidable rivals of Catholics in this regard were the Cathars. They not only had their own clergy and hierarchy, but also theology. Their favorite scripture was the gospel of John. They translated it into the national languages of those countries where they were supported by the population. The text in Occitan has come down to us. In it, they adhered to the version of the Prologue translation that was rejected by the official church, believing that this could justify the existence of a source of evil opposing God. In addition, in interpreting the very 15th chapter, they emphasized the fulfillment of the commandments and holy life, and not the observance of dogma. The one who follows Christ is worthy to be called His friend - such a conclusion they made from the Gospel of John. The adventures of various

interpretations of the text of the Scriptures are quite instructive and indicate that any interpretation of the Bible can be used both for the benefit of man and to his detriment.